This blog entry was written by Paul Richards, one of our core group members. Paul and his wife Melissa, steward of one of the most impressive bluff prairies in our area (Pleasant Bluff). Paul has generously contributed some thoughts on history, the state of our present ecology, and where we are (hopefully) headed in the future.

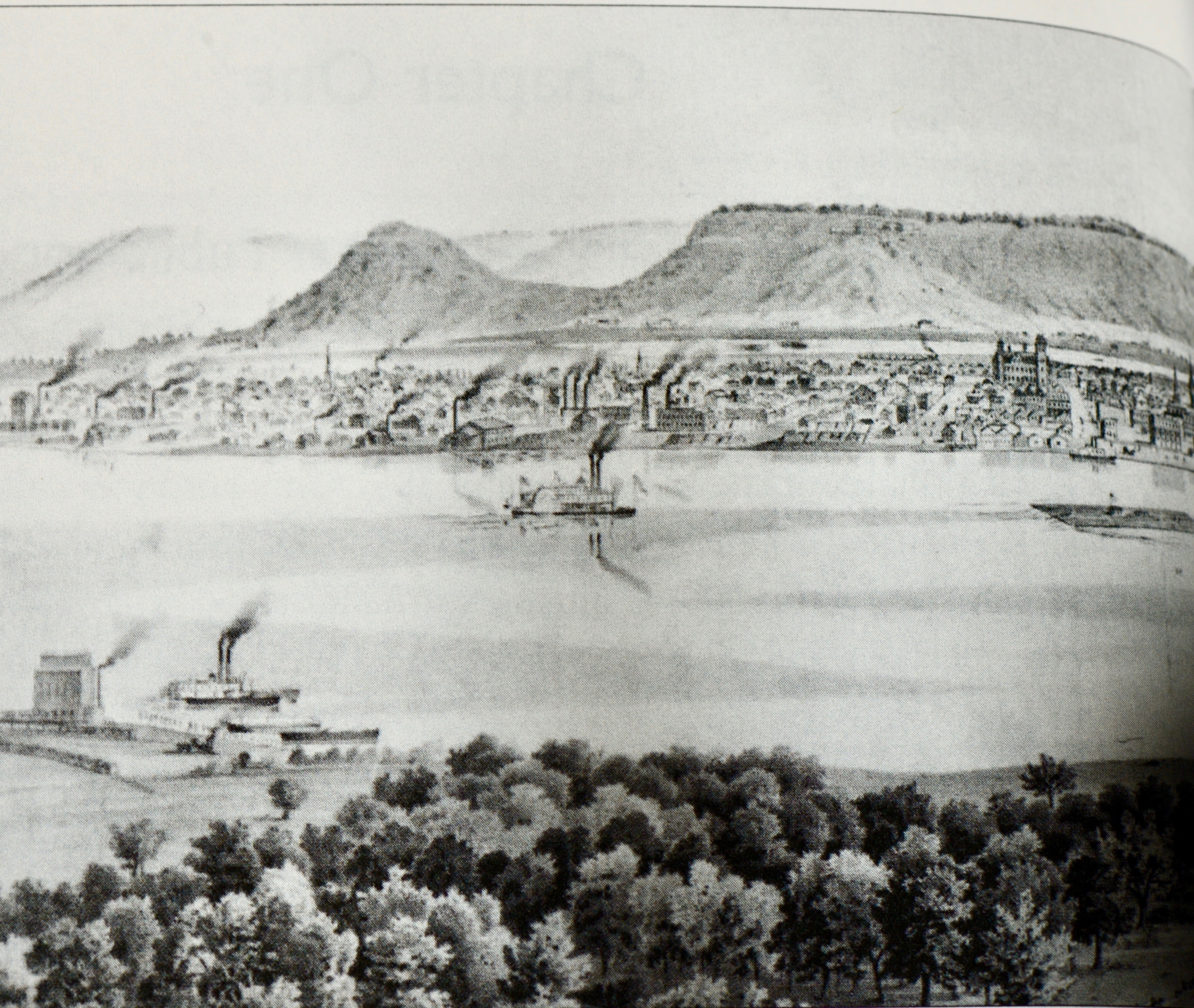

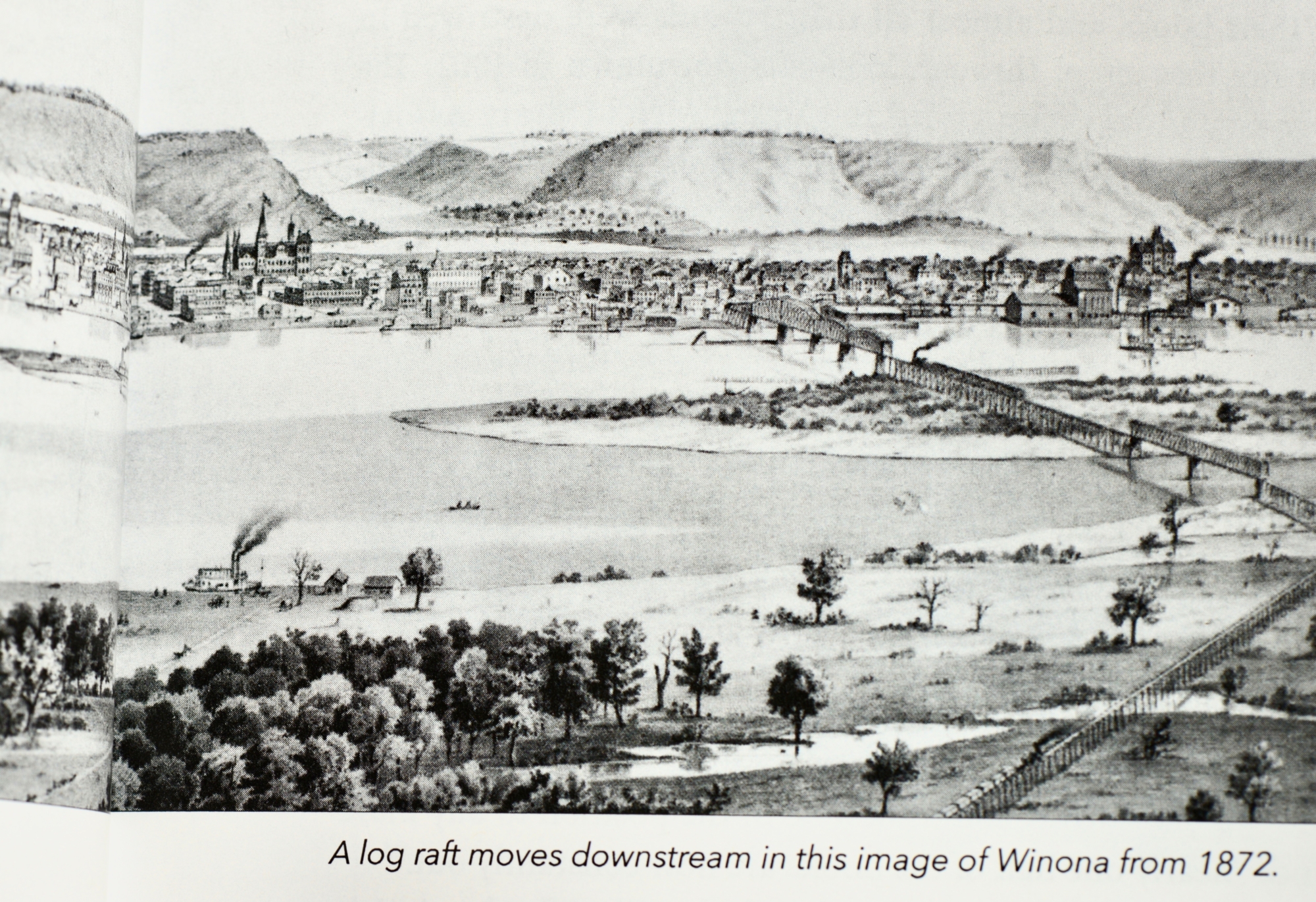

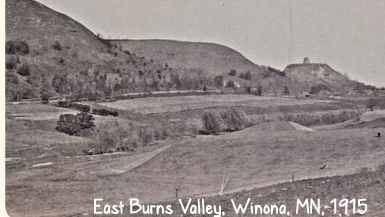

Our local community, known to previous inhabitants as Keoxa, Montezuma, and also (fittingly) as Wapasha’s Prairie, was once primarily a grassland. Before European settlers arrived here, grasses, forbs (wildflowers), and sedges thrived across the landscape, especially on the southern facing sides on the bluffs. Savannas of oak mingled with the prairie were also to be found along the north sides of the bluffs and along the valley floors. In other spots, Ice Age plants survived from the aid of the bluff slopes “breathing” cold air out on them (look up ‘algific talus slopes’). Cedars and junipers gripped the rocks of the upper prairie edges where they were protected from fire. These remnant prairies and their distinct plants can still be seen on a few of our bluffs. Some have so far managed to survive on their own despite the onslaught of woody invasives. Some are being assisted by dedicated people.

The prairies and bluffs saw a radical change when Europeans settlers arrived. With them came new plants, livestock, and techniques of managing the land. The biggest impact was, perhaps, fire suppression. A land that was once allowed (even encouraged) to burn by the Indigenous peoples was allowed no more. Fire started both by native peoples and nature (via lightning) were a vital part of our local ecology. This was as true for the native plants as it was for the people that lived here. Fire initiates vigorous wildflower and grass growth that then attracts the animals that need these plants to survive. Animals such as bison, elk, and deer were major parts of the native peoples’ diet. Due to the more recent absence of fire (due as well to overhunting), many of those animal species have disappeared from our landscape. Less fire led to woody plants being able to march across the landscape, creating a shady canopy above the sun-loving prairie plants.

Settlers with a hunger for lumber, decorative yards and shade, hastened this spread by bringing seeds from trees and from other plants with them from the East. Some of these plants were highly invasive with no native population controls here to keep them at bay. In our area buckthorn currently finds itself the most scorned of the invasive plants with bittersweet coming in at a close second. There is even a threat to our prairies from some of our native species. Cedars and junipers have choked out many of our slopes because there has been no fire or grazing to keep them in check.

Many current landowners are now realizing the value of what has been lost and are trying to bring back these prairies. We are beginning to see the return of the bluff prairies through the use of techniques that include clearing of woody vegetation and careful application of herbicide. We are also slowly recognizing that fire and grazing animals are truly integral components to prairies and are necessary for the success of our restoration efforts.

Hopefully future generations will see a landscape that more closely mirrors (in both beauty and function) the landscape we have only seen in old photos and sketches from the past. This will only be accomplished through bringing historical practices into alignment with our current efforts of restoration and through a persisting land stewardship model.

Leave A Comment